Released 2014. Directed by David Fincher. Screenplay by Gillian Flynn, adapted from her novel of the same name. Starring Ben Affleck, Rosamund Pike, Carrie Coon, Kim Dickens, Tyler Perry.

There’s no discussing Gone Girl without giving everything away from the first sentence, and this review leaves no plot point unexposed. Trust me, just see the film.

David Fincher is infamously exacting. While shooting Zodiac, his demand for precision and detail, expressed through shooting scenes upwards of 70 times before moving on, came under fire from some of his actors. It wasn’t the first time, and it won’t be the last. His response was simple: “The first day of production in San Francisco we shot 56 takes of Mark and Jake – and it’s the 56th take that’s in the movie.” Fincher knows what he wants to achieve, and won’t leave until he has it. For the viewer, it’s reassuring. I feel confident that what I see in a Fincher film is exactly what is meant to be there. Everything is deliberate and necessary.

What this means it that there exists nobody better suited to direct Gone Girl, a crime drama that is about, above all else, image management. Nothing is left to chance. It feeds us information slowly and deliberately, making us suspicious of every gesture, every line of dialogue, every pause. Sets are somehow bare and devoid of action, yet we know that there’s detail and purpose in everything, because we know Fincher.

It’s what any good mystery ought to be, but Gone Girl goes further. It’s not just about a how a woman disappeared and who’s responsible. Solving the crime is just part of the story. Gone Girl is about how the story is told. The different versions different people see or are given. How and why we lie or deceive. What we want others to know and how we get inside their heads to construct narratives they’ll believe. How people change, what they hide from others, how it comes out, rapidly over days or gradually over years, and the difficulty in knowing someone, or even knowing how much you know about them. It’s about the importance and power of perception and representation.

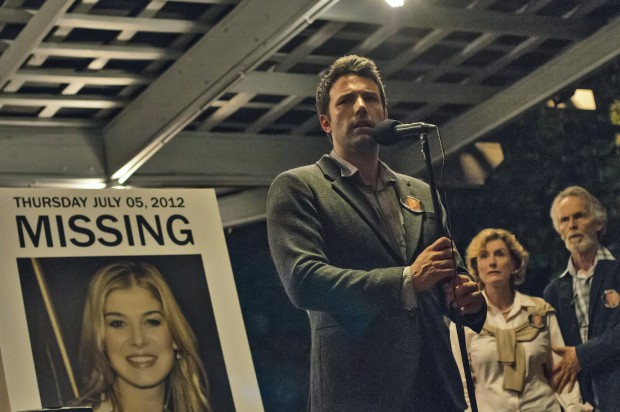

On his fifth wedding anniversary, Nick Dunne (Ben Affleck) reminisces with his sister Margo (Carrie Coon) about his deteriorating marriage to Amy (Rosamund Pike). Entries from Amy’s diary tell us in flashback about their charming, perfect courtship, the use of her life as raw material for her parents’ book series, Amazing Amy, the loss of her and Nick’s jobs in the recession, their move from New York to Nick’s small hometown in Missouri and their new life in the American Midwest. Returning home after a phone call from a neighbour, Nick finds Amy absent and furniture smashed. He summons the police and two investigations begin: one by Detective Rhonda Boney (Kim Dickens) into Amy’s disappearance, the other by the national media into Nick.

The one thing people should know before seeing Gone Girl is that it’s no police procedural, and it’s barely a whodunnit. To think that there are clues hidden away in the deliberate detail, to be unveiled in a climactic reveal, is not only not really the case, it misses the point. Don’t look for clues. Don’t attempt to solve the crime before the big twist. Though the film focuses on an investigation into a disappearance, and indeed is full of evidence and exhibits (a maxed out credit card, a burned diary, a bloody blunt instrument), it’s all about people, not breadcrumbs. It actually goes out of its way to make a point of this: an envelope marked “Clue One”, found early on in a bedroom drawer, looks like the catalyst for a Seven-style hunt for a criminal with a genius plan. Not so, we’re soon informed – the envelope is merely part of a treasure hunt Amy sets up for Nick on each anniversary, so although it’s worth following up on, and we do indeed track it to clues two and three, it’s not the product of a mastermind. Until we find out that it is.

It’s revealed that Amy planted the clue as part of her scheme to frame Nick for her murder, a reversal that indicates just how much Gone Girl is eschewing crime narrative convention. The envelope hasn’t just been planted by Amy. It’s been planted by the film to emphasise that playing the procedural game is not the point. The envelope genuinely is important, and it’s something that a procedural would zoom in on and enhance and test for DNA and fingerprints without delay. Gone Girl deliberately puts it there so that it can direct us away from it.

We’re watching a film about why, not how. Indeed, the big reveal of how Amy has faked her death, while impressive and an exciting set-piece of a monologue, is given to us in one go, in the middle of the film. We’re not figuring it out along the way, it’s packaged neatly and almost thrown away, and it’s not the end of the story. Far from it.

Gone Girl also departs from the procedural and whodunnit genres by refusing to furnish us with possible suspects. There are four realistic possiblities: Nick, Amy, Amy’s old boyfriend Desi (Neil Patrick Harris) and literally any homeless person who might have broken in. These possibilities aren’t juggled and kept at the front of your mind as you might expect – for the first half, the film wants us examining, and increasingly suspecting, Nick alone. Actually, it arguably fails. The film wants us to see, to an extent, what the media always sees: a missing wife and a presumably guilty husband. But I think that what little we’re shown of Nick when he’s away from the prying eyes of the police and press makes it difficult to ever really believe that. We see his reaction of surprise to the broken furniture as he returns home – it’s not a performance, he’s reacting alone. We know that he calls the police right away and appears to cooperate. He’s admittedly calmer than you’d think an innocent person ought to be, but that initial reaction set me up for never really thinking he was responsible. That the film seemed to be pushing so hard for me to suspect that Nick was bluffing his way through the police investigation, to believe that he was so detached because everything was going to plan, also felt too simple. Had the film been setting up to reveal Nick’s guilt, it would have been a huge disappointment. There would have been no twist. Gone Girl isn’t a whodunnit at all – as I mentioned, there aren’t many characters who could have dunnit – but to tell a down-the-line story with no twist would have been a generic betrayal too far.

(Mind you, there’s so much subterfuge and hiding of intentions here that I can’t honestly tell you that a version of the story in which Nick was guilty wouldn’t have been terrific. I can’t imagine what it would have been, but I’m sure it could have been good. My lack of belief in Nick’s guilt wasn’t because I couldn’t imagine that story – I’m easily and happily wrongfooted all the time, and I delight in not knowing what’s coming next. I just felt sure it wasn’t going to be that simple.)

The difference between reality and image, and the importance of the full story, is brilliantly illustrated several times, such as with Nick’s unfortunate photograph with a stranger. At a hastily-arranged press conference to inform America of his missing wife, Nick is suddenly hounded in an otherwise empty corridor by a woman who asks him to pose for a selfie with her. He is manifestly uncomfortable as she forces herself beside him and points her camera towards them, but instinctively polite, he cracks a smile. Seeing it occur in motion, we know that it’s an awkward smile, one into which he is coerced, and which lasts only split-second before Nick’s expression returns to its prior, blank, state – but there’s a photograph of it now. It’s a heavily charged moment. It meant nothing, he was ambushed into it, but Nick quickly realises that it won’t look that way to anybody else, including the media, and he asks the woman to delete the image. She refuses, and he makes a weak attempt to snatch her phone. Annoyed, she leaves, asserting that she’ll share the photo with whomever she likes, and sure enough, it’s soon all over the news, run in pieces attacking Nick for flirting with a stranger during a press conference for his missing wife.

The message is clear: Context is everything, and when context is stripped away, image is everything.

Nick flashes that same awkward smile during the press conference, when told to by a photographer.

Nick flashes that same awkward smile during the press conference, when told to by a photographer.

Gone Girl doesn’t only contend that how people present themselves and are perceived by others is important in media or legal proceedings. We’re shown, in flashback, Nick and Amy’s meet-cute and later Nick’s proposal to her. In both we see a version of Nick that is different to how we’re shown him at other times. He’s flirtatious, overtly charming, light-hearted. Throughout the film he’s shown to be quick-witted and attentive, but in these flashbacks he’s using those qualities to make Amy laugh rather than point out, as he later does, details and problems with a police investigation into him. The point is that he’s selling Amy a version of himself that she marries. Nick’s not lying about who he is; he’s in circumstances and facing incentives that bring out a version of him. And as he and Amy lose their jobs and their relationship begins to encounter rocky territory, a different version of him emerges, one with blemishes and failings, and the marriage declines.

I’ve never been truly sold on the visual aesthetic that Fincher’s developed since his move to digital filmmaking. There’s no question that it’s deliberate and the guy knows what he wants to achieve, but in a way that makes it worse – there’s a fogginess, a lack of clarity to his images that in the hands of a lesser filmmaker one could easily ascribe to lack of experience or talent. And that they’re so accomplished puts the lie to that – shallow focus is combined with rapid racks to different planes and characters with extraordinary timing and precision. Only when specifically watching for it did I even notice. That so much of the frame is typically out of focus, especially the foreground, is a contributor to this feeling of fogginess, and it is so deliberate. Having watched for it, I find it difficult to get over how perfect the camerawork is.

With Fincher I know there’s a purpose, but I don’t know if finding the images unpleasant to look at and difficult to appreciate detail in is part of that. Areas of shadow are near impossible to resolve in a way that they weren’t in a pristine print of Seven, a visual symphony of darkness, that I was once lucky to see. At times I can grasp the use of the aesthetic: Nick and Amy’s flirtatious meeting, given the Fincher visual treatment, is an off-kilter scene, dominated by an ill, green-yellow hue (and underscored by equally unsettling music from Trent Reznor and Atticus Ross). It feels like a visual warning for the relationship’s future health. And in the film’s one truly beautiful scene, Nick and Amy’s romantic peak of a kiss under falling sugar, the aesthetic is adapted, diminished, less invasive. To highlight poetic beauty in a single scene within a film dominated by a tenebrous, discomforting visual veneer is a wonderful and smart way to show us how Nick and Amy’s relationship never lived up to that moment, and to render more believable and reasonable Amy’s extreme reaction to seeing Nick share a similar moment with another woman. And there’s no question that something about Fincher’s work would be lost were he to forgo this look. Discomfort, suspicion, hidden motives and distrust come up in his work time and time again, and that vaguely foggy feel to his images certainly articulates that in a quietly visceral way.

There’s also something deliberately digital about Fincher’s visuals – not because they’re filmed on digital equipment, which now totally dominates cinema and is the basis for extraordinarily beautiful work in a number of films, but designed into them to reflect a feeling of unease and constancy of screens and images in the digital world. It’s not doing the same thing as, say Michael Haneke’s Caché, which in 2005 brilliantly (if not prophetically) blurred the lines between cinematic, televisual, home video and security images, converging ever more rapidly, to generate an ambience of persistent threat that one never knows quite what one is looking at, who is looking at them, and how to interpret what one can see. Fincher doesn’t want us suspicious of the truth of what his images show us in the same way that Haneke does, but the world of Gone Girl – i.e. everything we see and hear, especially set design, score, shot composition, costume and action – is somehow bare, limited, stripped down with the effect of emphasising the filter through which it’s observed. It evokes a sense of perpetual unease brought on by the digital domain, a world that doesn’t want to hide seams and provide enveloping experiences but rather fights for your increasingly segmented attention aggressively and hungrily. It confirms your eternal awareness of its machinations.

In short, Gone Girl knows it’s being watched.

So far, so good, right? It’s tough to argue that Gone Girl isn’t consummately made, a technically brilliant achievement. But it has problems.

Gone Girl is a film that occupies some uncomfortable territory when it comes to gender representation and feminism. Calculating and possessing power over men, Amy is a men’s rights activist’s dream. She’s a modern evolution of the femme fatale – where her historical counterparts seduced men through irresistible sexual allure, Amy does so through manipulating a society and media that believes and wants certain things. At first she tries to tell the story of the terrified, beaten wife, locked into a marriage with a husband who ultimately kills her. When circumstances conspire against her, she improvises a story of kidnap by a former lover, one that involves significant sexual abuse and justifies her murder of her captor. Gone Girl understands the world in which it exists just as much as she does – when Amy spins the FBI her rape story, only Detective Boney is suspicious of her and wants to interrogate her; the officer in charge explicitly shuts her down and tells Amy, “you can’t blame yourself”. Finally, she imprisons Nick in a relationship by becoming pregnant with his child without even needing him to touch her – she makes use of an old sperm sample of Nick’s. Pregnancy and childbirth is perhaps the ultimate expression of women’s difference to men (not to mention an area in which women are overwhelmingly favoured by the legal system), and Amy not only sees that and uses it, she does so without needing to seduce anybody (more of which in a moment). Everything that is blown out of proportion and feared about feminism – or rather, the absurdly corrupted image of feminism that many people hold – is built into Amy. She knows precisely how to manipulate the machinery developed by feminism, intended to improve gender equality and human flourishing, for her own ends, and does so ruthlessly, in doing so giving those who feel threatened by it something to latch on to.

It’s important that Margo and Detective Boney are women, but I think it’s cynical. Margo, it seems, never liked Amy, while Boney refuses to buy into the murderous husband story without sufficient evidence. Even when she eventually arrests Nick after finding Amy’s diary, she doesn’t leave the case alone, wondering why the diary wasn’t burned to the point of being unreadable. These are two women who refuse to buy into Amy’s media-friendly narrative, but although it’s very clear that their gender is important it’s difficult to see what the film is trying to do other than make its gender politics seem more complex. Were Margo and Boney men, I don’t think the film would be substantively different. Their roles in the plot are important, but their roles as women are cosmetic.

Sex in Gone Girl exists for anything but love and procreation. Amy doesn’t need to use it to become pregnant. During her magical first date with Nick, it’s cunnilingus that we see her enjoy, not penetrative sex. The only time she has sex is when she needs physical evidence from Desi to sell her story of rape, and once she has what she needs, she kills him. This all looks like boilerplate femme fatale characterisation, but it’s a little more complicated than that. Amy’s intercourse with Desi is an adapted form of a femme fatale‘s seduction: an old, somewhat obsessive boyfriend of hers, he would be easy to sleep with if that were her purpose, but it isn’t. She resists him, and when she does so, his response is only to say, “I won’t force myself on you”. (It’s said in a frustrated way, one that subtextually demands Amy let it happen, but it goes no further and Desi leaves it. But more than that, he’s weak, emasculated. It’s questionable whether he really could bring himself to force himself upon her.) When a high-profile television interview of Nick is broadcast and it is immediately clear that it’s destined to restore his name in the public’s perception, as well as that it contains hidden messages from him to her, Amy needs to do something different in order to win, and it’s only once she has that goal that she has sex with Desi. Amy isn’t seducing a man who would otherwise not have sex with her. She withholds sex from a man desperate to sleep with her until it gains a purpose.

It’s worth bearing in mind that the situation with Desi is one that could be genuinely hideous for Amy. She’s living in the secluded lake house of a man who has desired, followed and waited for her for two decades, furnished with the kind of expensive, high-class luxuries that scream that she’s being controlled and imprisoned by him, closed-circuit TV cameras surround the property (ostensibly to ensure its security but conceivably to keep her from leaving) and nobody but the two of them knows they’re there. Amy finds herself slightly surprised by this, and is initially thrown by just how dangerous the situation seems, but Desi, while unsettling, is tame. Inert. Even when Amy does eventually take him to bed, he doesn’t want the rough sex she does, asking her to “go slow” (her purpose, of course, is to cause physical damage to herself for her future medical examination). She needs to adapt to her new environment, improvise and change her story, but Amy remains absolutely in charge.

(It’s a problem that Desi is a character who deeply echoes a historical coding of homosexuality in Hollywood – including his sexual inadequacy – and that he is played by Neil Patrick Harris, perhaps the highest-profile openly gay actor in Hollywood today. I don’t claim that this is the reason for his casting, and there are other factors, such as his best-known character, How I Met Your Mother‘s Barney Stinson. Barney is an impossibly wealthy, creepy philanderer; Desi is an impossibly wealthy, creepy stalker, and the baggage Harris takes from the one may inform the other. Nonetheless, Desi fits comfortably into that uncomfortable tradition.)

Related to the core issue of gender representation is the problem that Nick is far too likeable. Even when it’s revealed that he had been cheating on his wife for over a year, that he had gone as far as copying the sugar kiss (a story Amy tells, admittedly, but one of the few that I think is presented as the truth), it’s hard to hate him. He is constantly associated with truth and honesty – despite keeping his affair a secret – while Amy is a liar. When going through Amy’s diary, the police ask Nick to confirm or deny various things written in it. He could be lying when he does so, but we don’t get that impression. When he says it’s the truth, it’s the truth. His crimes – cheating on Amy, turning into a slacker after losing his job, and moving her to Missouri – aren’t quite on the same level as Amy’s attempted framing of him for her murder, and it never feels like the film is trying to convince us that he’s even partially at fault. Given what we see of Amy, of course the relationship fell to pieces and he cheated on her! She’s a nightmare! When he finally snaps and attacks Amy, shoving her against a wall when she teases him that his unborn son will grow up to hate him, it’s distressingly cathartic, a brief release of anger that Nick is totally justified in feeling. It should be unacceptable, but it feels deserved. It’s incredibly troubling, in part because it’s ambiguous. I can’t work out what the film’s purpose is, and that might be the biggest issue overall. I don’t know what the film is trying to say.

I should be clear: I am in no way suggesting that these are things that a film should be prohibited from expressing or supporting. Art ought to be a space wherein anything can be openly discussed. I’m not saying women should never be presented as evil and audiences should never be directed to hate them. And Gone Girl is clearly not blindly staggering into these troublesome areas. It’s not creating problematic gender representations without realising it like most commercial art does. Gone Girl knows the ground on which it’s treading. But if it’s meant to be satire then it’s failed satire, just as Fincher’s Fight Club was (no film that satirises masculinity through its transformation into a destructive anarchist collective should end with the audience feeling pissed off at being told that the destructive anarchist collective was Very Bad). If there’s some motive in Gone Girl to mock the kind of people who believe that women hold too much power and that feminism is evil, through constructing a femme fatale who encompasses all of their fears and enacts an incredibly complicated and unbelievable scheme, then it entirely fails. Because Amy and her plans aren’t absurd enough to expose these beliefs as ridiculous. At worst they enhance them. And if it’s not meant to be satire then it’s ultimately very troubling.

All of this leaves me conflicted about Gone Girl. It’s very tightly constructed and makes me squirm non-stop for two and a half hours, and it has made me confront what I think like no other film this year. But I’m hesitant about it, because of how unclear it is about what views it’s really espousing. It might be trying to be satire, it might be cynically looking for controversy, it might even be saying what it really thinks. I can’t tell, and that’s deeply unpleasant when its themes are so important. But then nobody goes into a Fincher film expecting platitudes and easy ways out. Maybe the fact that it’s caused me such distress in trying to work out what I think is the best recommendation I can give it.

One comment