I twice discussed Phantom Thread in my podcast back in February, and this brief post is a development of an observation I brought up in those conversations. You can listen to the discussions here (the second screening involved my brother who was already a huge fan of the film, having seen it five times at the cinema, by the time I’d seen it twice): Part 1, Part 2.

When I saw Phantom Thread in the cinema I was struck by how it visually emphasised verticality and compressed the frame horizontally. It felt like an Academy ratio film. The film is certainly echoing or adapting classic Hollywood style, with its period setting, rich romantic plot, extraordinary orchestral score and closing credits that conspicuously fade over the top of each other. Paul Thomas Anderson only went so far; he didn’t shoot in black and white or Academy ratio (in evoking the milieu, there’s a deep chasm between serious and corny), but I think he did a lot to create an Academy ratio feel within a widescreen frame, by choosing an appropriate location and using it in conjunction with the camera to make the frame feel tall and narrow.

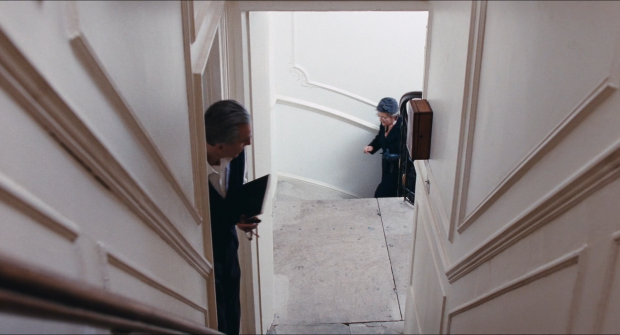

It’s in the general setting, a townhouse in London with narrow corridors, tight staircases and high ceilings – you rarely see ceilings in Phantom Thread at all, the walls stretching all the way to the top of the frame giving a feeling of limitless height. There’s an interesting balance of tone achieved, too – with walls everywhere, the Woodcock residence is kind of a prison, but not an inescapable one, as there’s always the possibility of movement upwards. There always seems to be a staircase leading up and out of frame. Imagine how putting a lid on the image would affect it. (The omelette scene is the most notable exception, shot in part from below and angled upwards, the ceiling in frame at points, dramatic lighting and contrast all contributing to the drama of the climax.)

It’s in the details of the set design, particularly in the scene in which Alma ‘treats’ Woodcock to dinner and a fight, with thin wooden borders (I don’t know if there’s a term for them) lining the walls behind the characters, stretching up into the heavens. They’re spaced out behind Woodcock, framing him quite narrowly, and a candle in the foreground to the left of frame helps to both emphasise verticality and block off a portion of the frame, with Alma on the right of frame doing the same, creating a subtle frame within a frame of narrower aspect ratio. The long lens compresses the space and gives the characters, in their individual shots, terrifying, towering dominion over the audience. This scene, like the tangentially mentioned omelette scene, is shot from below, but in the tall, narrow Woodcock residence, there’s no lid to ensure the pot fully boils here. (Though during the gruesome argument that takes place, one deeply feels the lack of a staircase.) Compare the shapes in the set dressing, the way they help to narrow or widen their frames: tall, thin candlesticks and wall decoration in the dinner scene; low, wide bowls, a wide lampshade, and a horizontal hanging rack on the wall in the omelette scene. The technique of blocking off the edges of the frame is used in other shots around the Woodcock residence, with door frames and walls sat out of focus in the foreground – they’re not the focus of the shot but they’re very important in creating shape. Again, imagine those shots without the left and right parts of the frame filled with unexciting blurry doors and walls. The house would feel so much wider, less claustrophobic; perhaps freer, less bound by Woodcock’s rules and idiosyncrasies. And far from the classic Hollywood look being evoked. It might even feel, dare I say it… ugh, modern.

In fairness, this was a feeling I felt much more strongly in the cinema than I do on home media. The image dominating your field of vision, you sat quietly beneath it, a slave to it, helps to emphasise all this verticality. It isn’t nearly as effective if you’re watching on TV, but, well, you should have gone to see it at the cinema. And it’s not everywhere in the film, far from it – plenty of shots of nature, dinner parties and so on don’t share this particular feeling, but it dominates the Woodcock residence, which in turn dominates the film.

And, finally, there’s that toilet shot, the weird culmination of Woodcock’s and Alma’s awful, toxic, fairytale, beautiful, insane story: a slow track in which begins with the sides of the frame in almost total darkness, creating a near-perfect Academy ratio frame.

Anyway, this has been on my mind for a while and now I’ve gone and collected some screenshots to show you what I mean and prove to myself I’m not crazy. They’re presented here in chronological order as they appear in the film. Enjoy.

Reblogged this on First Impressions and commented:

For those wanting to follow threads on Phantom Thread